The following is an excerpt from the Art of Scalability as a design approach to mitigate the effects of a Data Center or Regional failure such as the AWS-East-1 outage on October 20, 2025.

“Whoa, hang on there!” you might say. “We are a young company attempting to become profitable and we simply cannot afford three data centers!” What if we told you that you can run out of three data centers for close to the cost that it takes you to run out of two data centers? Thanks to the egalitarianism of facilities created by IaaS (“public cloud”) providers, the playing field for distribution of data and services has been leveled. Your organization no longer needs to be a Fortune 500 company to spread its assets around and be close to its customers. If your organization is a public company, you certainly don’t want to make the public disclosure that “Any significant damage to our single data center would significantly hamper our ability to remain a going concern.” If it’s a startup, can you really afford a massive customer departure early in your product life cycle because you didn’t think about how to enable disaster recovery? Of course not.

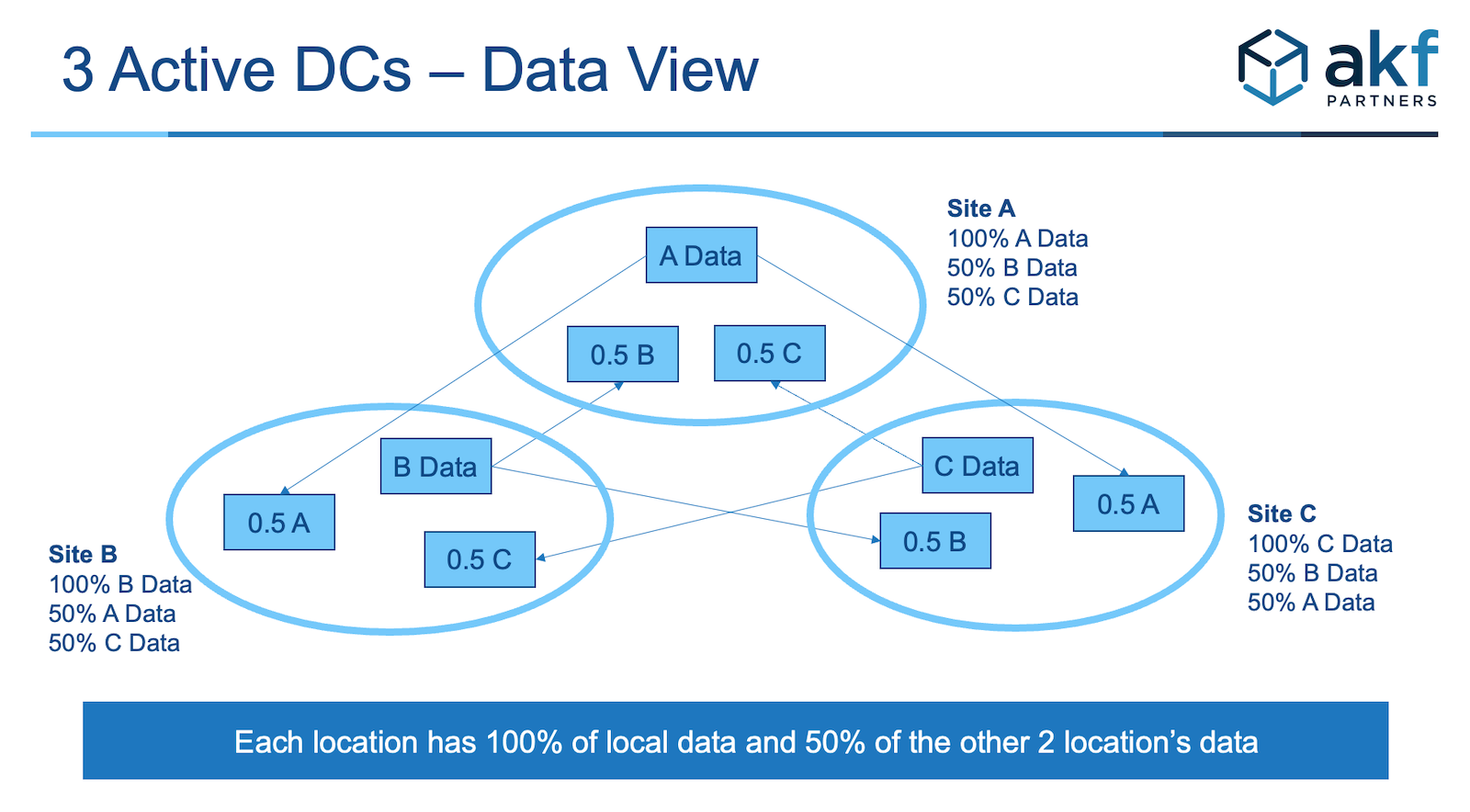

In Chapter 12, we suggested designing for multiple live sites as an architectural principle. To achieve this goal, you need either stateless systems or systems that maintain state within the browser (say, with a cookie) or pass state back and forth through the same URL/URI. After you establish affinity with a data center and maintain state at that data center, it becomes very difficult to serve the transaction from other live data centers. Another approach is to maintain affinity with a data center through the course of a series of transactions, but allow a new affinity for new or subsequent sessions to be maintained through the life of those sessions. Finally, you can consider segmenting your customers by data center along a z-axis split, and then replicate the data for each data center, split evenly through the remainder of the data centers. In this approach, should you have three data centers, 50% of the data from data center A would move to data centers B and C. This approach is depicted in Figure 32.4.

The result is that you have 200% of the data necessary to run the site in aggregate, but each site contains only 66% of the necessary data—that is, each site contains the copy for which it is a master (33% of the data necessary to run the site) and 50% of the copies of each of the other sites (16.5% of the data necessary to run the site, for a total of an additional 33%).

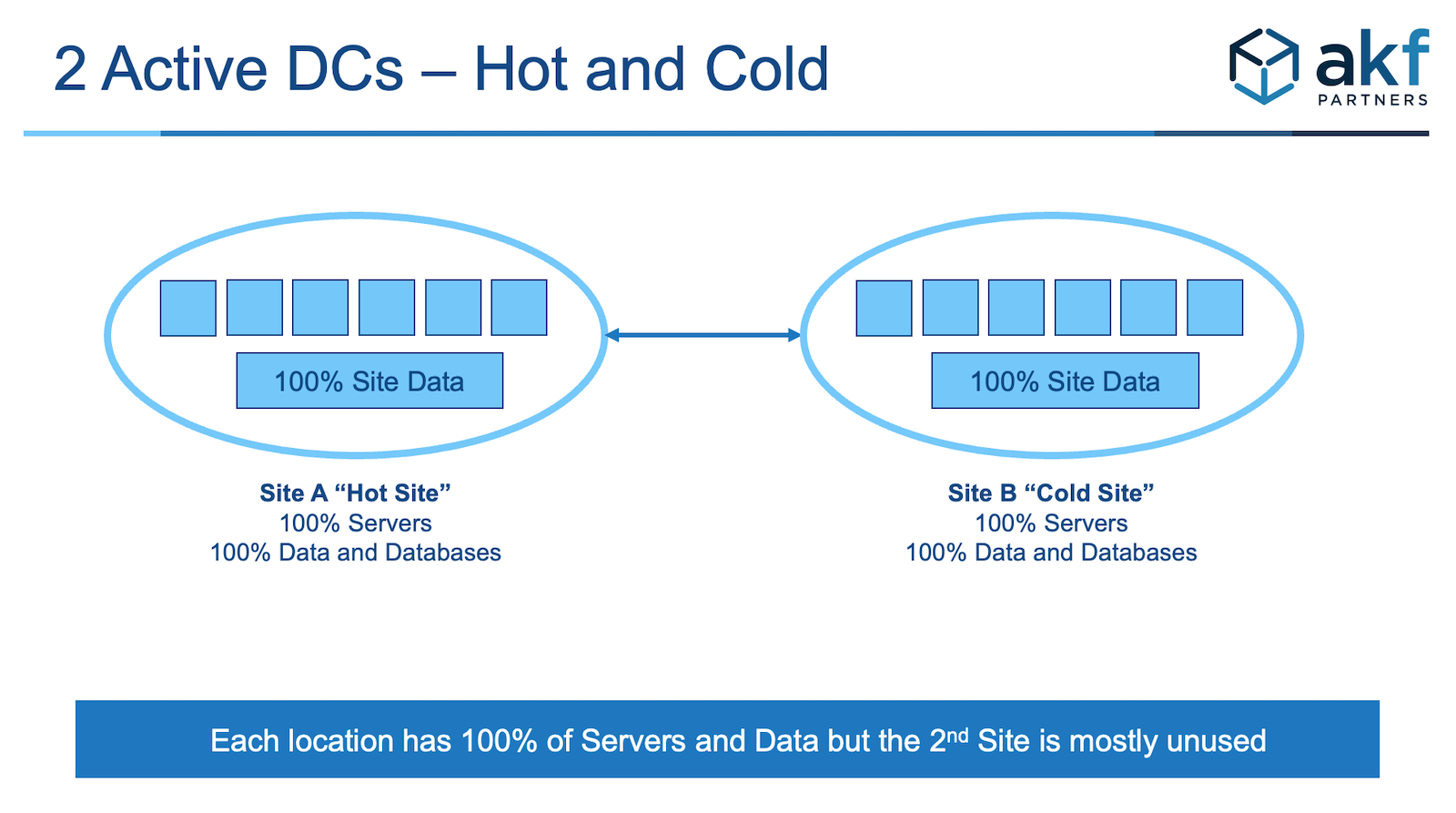

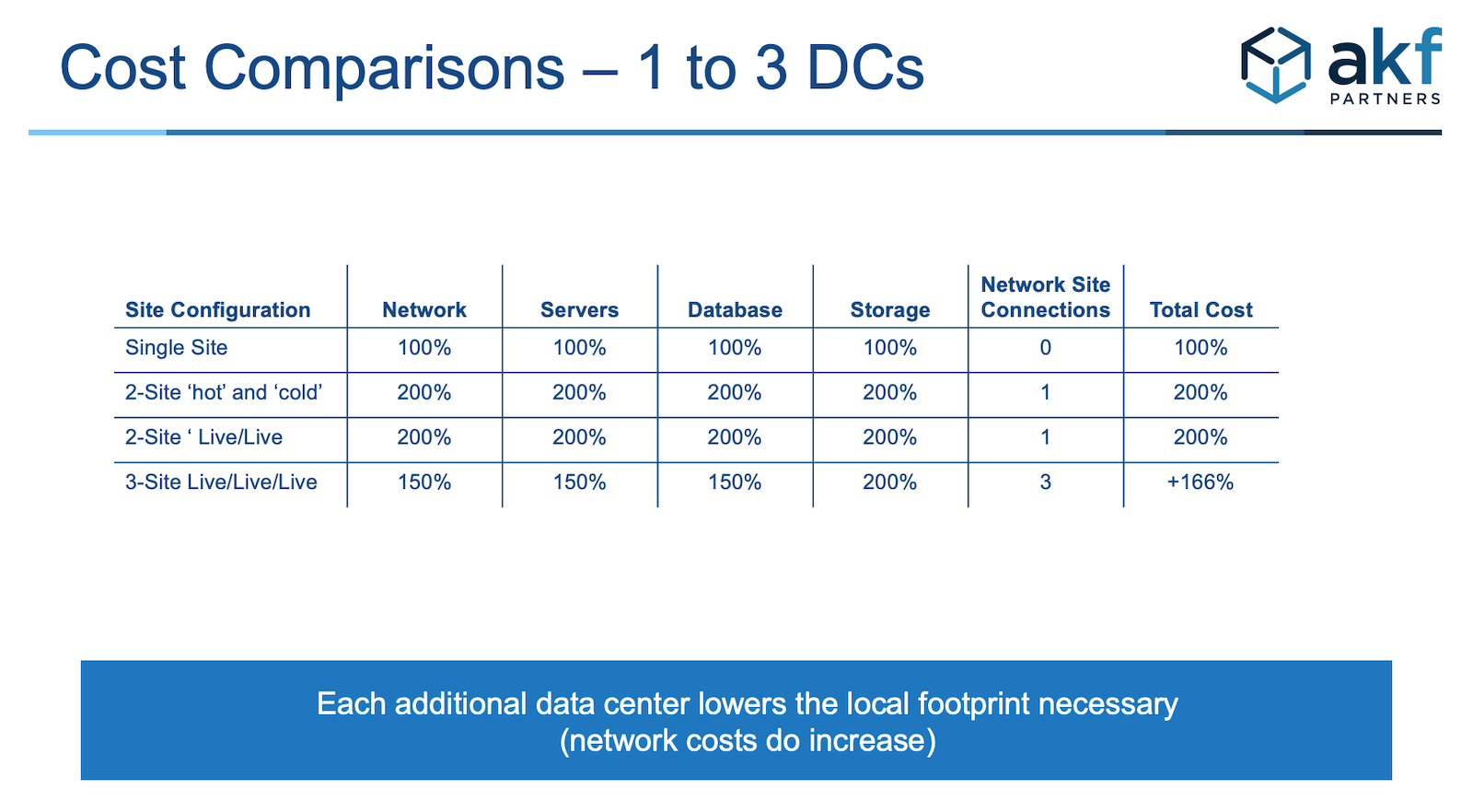

Let’s discuss the math behind our assertion. We will first assume that you agree with us that you need at least two data centers to ensure that you can survive any disaster. If these data centers were labeled A and B, you might decide to operate 100% of your traffic out of data center A and leave data center B as a warm standby. Back-end databases might be replicated using native database replication or a third-party tool and may be several seconds behind the primary database. You would need 100% of your computing and network assets in both data centers—that is, 100% of your Web and application servers, 100% of your database servers, and 100% of your network equipment. Power needs would be similar and Internet connectivity would be similar. You probably keep slightly more than 100% of the capacity necessary to serve your peak demand in each location so that you could handle surges in demand. So, let’s say that you keep 110% of your needs in both locations. Whenever you buy additional servers for one place, you have to buy the same servers for the other data center. You may also decide to connect the data centers with your own dedicated circuits for the purposes of secure replication of data. Running live out of both sites would help you in the event of a major catastrophe, as only 50% of your transactions would initially fail until you transfer that traffic to the alternate site, but it won’t help you from a budget or financial perspective. A high-level diagram of the data centers might look like Figure 32.5.

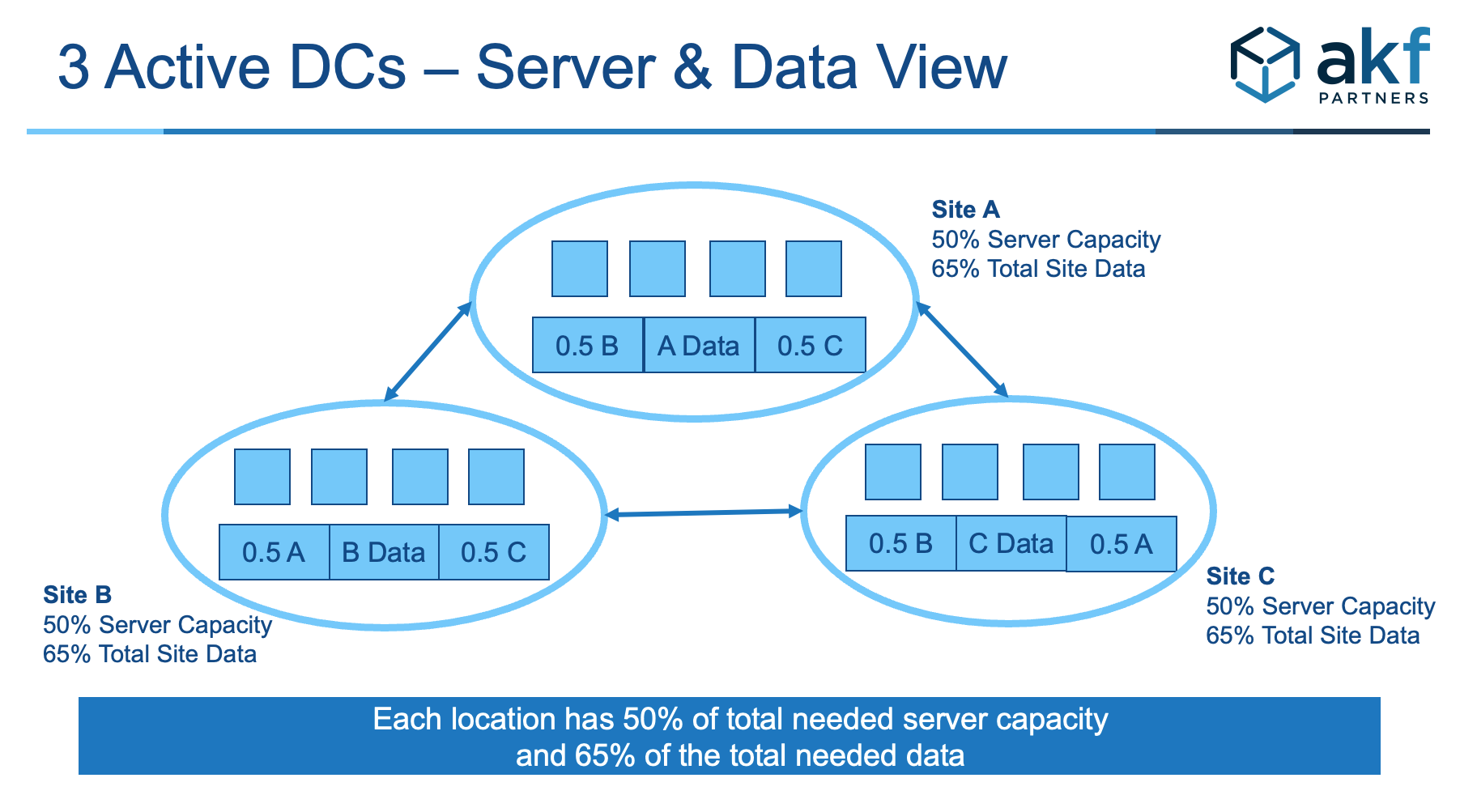

However, if we have three sites and we run live out of all three sites at once, the cost of those systems goes down. In this scenario, for all non-database systems, we really need only 150% of our capacity in each location to run 100% of our traffic in the event of a site failure. For databases, we definitely need 200% of the storage as compared to one site, but we really need only 150% of the processing power if we are smart about how we allocate our database server resources. Power and facilities consumption should also be roughly 150% of the need for a single site, although obviously we will need slightly more people and probably slightly more overhead than 150% to handle three sites versus one. The only area that increases disproportionately are the network interconnections, as we need two additional connections for three sites. Such a data center configuration is depicted in Figure 32.6; Table 32.2 shows the relative costs of running three sites versus two.

In Table 32.2, note that we have figured each site has 50% of the server capacity necessary to run everything, and 66% (66.66, but we’ve made it a round number and rounded down rather than up in the figure) of the storage per Figure 32.6. You would need 300% of the storage if you were to locate 100% of the data in each of the three sites.

Note that we get this leverage in data centers because we expect that the data centers to be sufficiently far apart so as not to have two data centers simultaneously eliminated as a result of any geographically isolated event. You might decide to stick one near the West Coast of the United States, one in the center of the country, and another near the East Coast. Remember, however, that you still want to reduce your data center power costs and reduce the risks to each of the three data centers; thus you still want the data centers to be located in areas with a low relative cost of power and a low geographic risk.

Maybe now you are a convert to our three-site approach and you immediately jump to the conclusion that more is better! Why not four sites, or five, or 20? Well, more sites are better, and you can certainly play all sorts of games to further reduce your capital costs. But at some point, unless your organization is a very large company, the management overhead of a large number of data centers becomes cost prohibitive. Each additional data center will provide for some reduction in the amount of equipment that you need for complete redundancy, but will increase the management overhead and network connectivity costs. To arrive at the “right number” for your company, you should take the example in Table 32.2 and add in the costs to run and manage the data centers to determine the appropriate answers.

Recall our discussion about the elasticity benefits of IaaS: You need not “own” everything. Depending on your decisions based on Figures 32.1 and 32.2, you might decide to “rent” each of your three data centers in various geographic locations (such as Amazon AWS’s “regions”). Alternatively, you might decide to employ a hybrid approach in which you keep a mix of colocation facilities and owned data centers, then augment them with dynamic scaling into the public cloud on a seasonal or daily basis (recall Figure 32.3). While you are performing your cost calculations, remember that use of multiple data centers has other benefits, such as ensuring that those data centers are close to end-customer concentrations to reduce customer response times. Our point is that you should plan for at least three data centers to both prevent disasters and reduce your costs relative to a two-site implementation.