The movement to SaaS specifically, and more broadly “Anything” (X) as a Service (XaaS) is driven by demand side (buyer) forces. In early cases within any industry, the buyer seeks competitive advantage over competitors. The move to SaaS allows the buyer to focus on core competencies, increasing investments in the areas that create true differentiation. Why spend payroll on an IT staff to support ERP solutions, mail solutions, CRM solutions, etc when that same payroll could otherwise be spent on engineers to build product differentiating features or enlarge a sales staff to generate more revenue?

As time moves on and as the technology adoption lifecycle advances, the remaining buyers for any product feel they have no choice; the talent and capabilities to run a compelling solution for the company simply do not exist. As such, the late majority and laggard adopters are almost “forced” into renting a service over purchasing software.

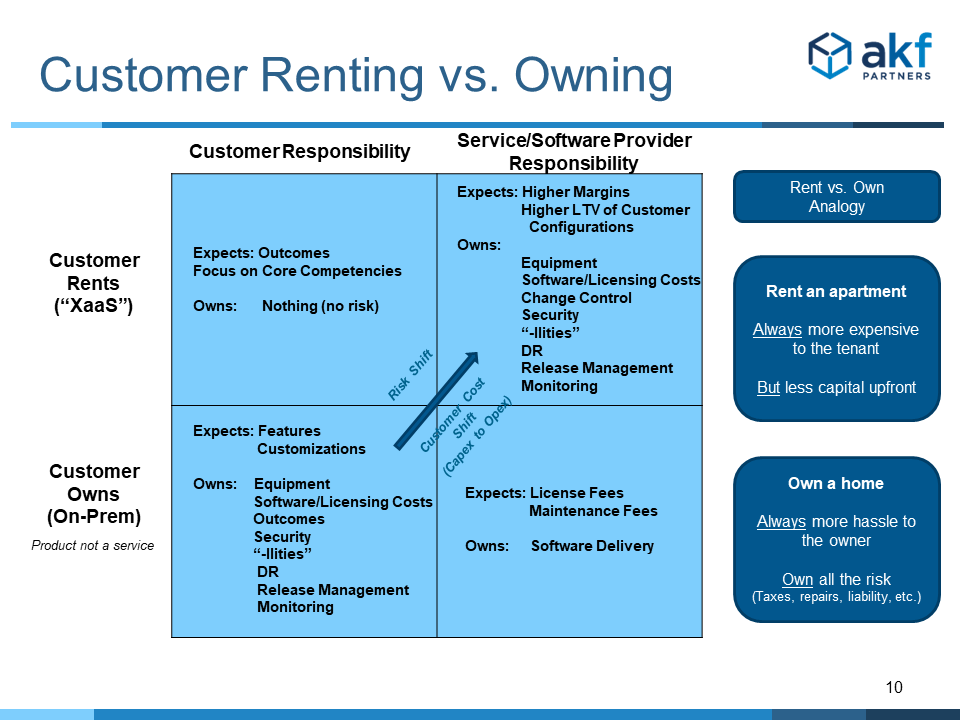

Whether for competitive reasons, as in the case of early adopters through the early majority, or for lack of alternatives as in the case of late majority and laggards, the movement to SaaS and XaaS represents a shift in risk as compared to the existing purchased product options. This shift in risk is very much like the shift that happens between purchasing and leasing a home.

Renting a home or an apartment is almost always more expensive than owning the same dwelling. The reason for this should be clear: the person owning the property expects to make a profit beyond the costs of carrying a mortgage and performing upkeep on the property over the life of the owner’s investment. There are special “inversion” cases where renting is less expensive, such as in a low rental demand market, but these cases tend to reset the market ownership prices (house prices fall) as rents no longer cover mortgages or ownership does not make sense.

Conversely, ownership is almost always less expensive than renting or leasing. But owners take on more risk: the risk of maintenance activities; the risk of market prices; the risk and costs associated with remodeling to make the property attractive, etc.

The matrix below helps put the shift described above into context.

A customer who “owns” an on-premises solution also “owns” a great deal of risk for all of the components necessary to achieve their desired outcomes: equipment, security, power, licenses, the “-ilities” (like availability), disaster recovery, release management, and monitoring of the solution. The primary components of this risk include fluctuation in asset valuation, useful life of the asset, and most importantly – the risk that they do not have the right skills to maximize the value creation predicated on these components.

A customer who “rents” a SaaS solution transfers most of these risks to a provider who specializes in the solution and therefore should be better able to manage the risk and optimize outcomes. In exchange, the customer typically pays a risk premium relative to ownership. However, given that the provider can likely operate the solution more cost effectively, especially if it is a multi-tenant solution, the risk premium may be small. Indeed, in extreme cases where the company can eliminate headcount, say after eliminating all on-premises solutions, the lessee may experience an overall reduction in cost.

But what about the provider of the service? After all, the “old world” of simply slinging code and allowing customers to take all the risk was mighty appealing; the provider enjoyed low costs of goods sold (and high gross margins) and revenue streams associated with both licensing and customization. The provider expects to achieve higher revenue from the risk premium charged for services. The provider also expects overall margins through greater efficiencies in running solutions with significant demand concentration at scale. The risk premium more than compensates the provider for the increased cost of goods sold relative to the on-premises business. Overall, the provider assumes risk for greater value creation. Both the customer and the provider win.

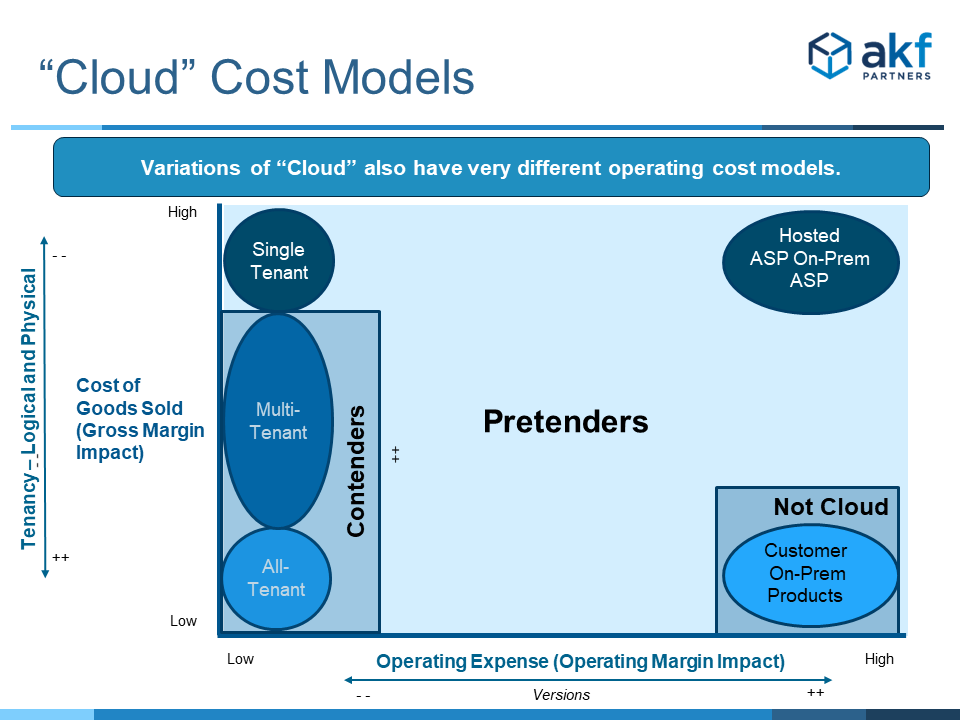

Architecture and product financial decisions are key to achieving the margins above.

Gross margins are directly correlated with the level of tenancy of any XaaS provider (Y axis). As such, while we want to avoid “all tenancy” for availability reasons, we desire a high level of tenancy to maximize equipment utilization and increase gross margins. Other drivers of gross margins include the level of demand upon shared components and the level of automation on all components – the latter driving down cost of labor.

The X axis of the chart above shows the operating expense associated with various business models. Multi-tenant XaaS offerings collapse the number of “releases supported in the wild” – reducing the operating expense (and increasing gross margins) associated with managing a code base.

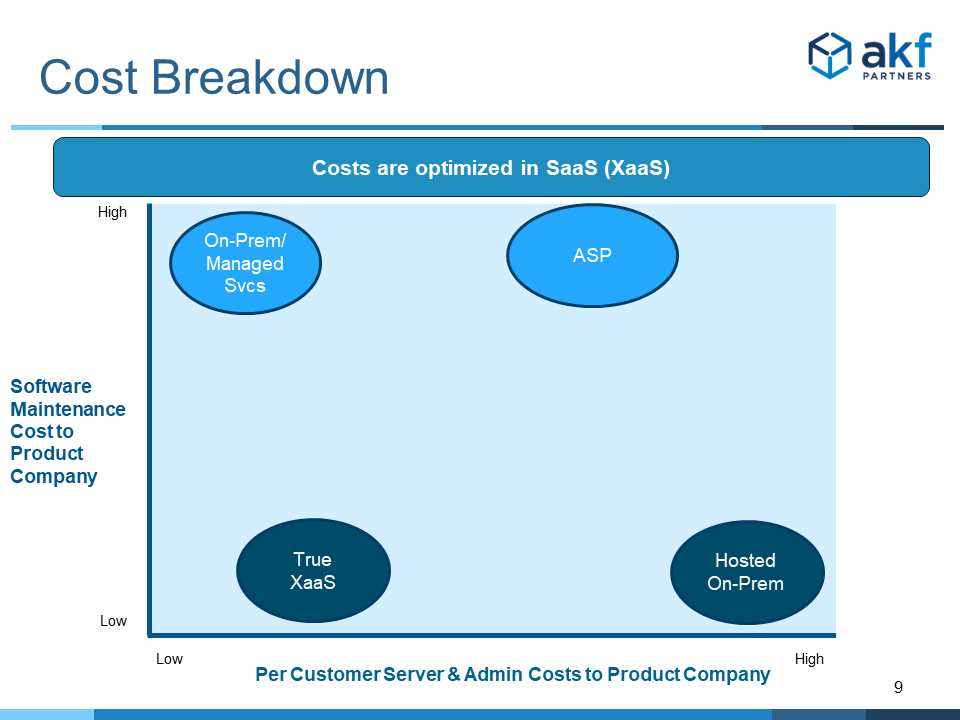

Another way of viewing this is to look at the relative costs of software maintenance and administration costs for various business models.

Plotted in the “low COGS” (X axis), “low Maintenance quadrant of the figure above is “True XaaS”. Few versions of a release reduce our cost to maintain a code base, and high equipment utilization and automation reduces our cost to provision a service.

In the upper right and unattractive quadrant is the ASP (Application Service Provider) model, where we have less control over equipment utilization (it is typically provisioned for individual customers) and less control over defining the number of releases.

Hosting a solution on-premises to the customer may reduce our maintenance fees, if we are successful in reducing releases, but significantly increases our costs. This is different than the on-premises model (upper left) in which the customer bears the cost of equipment but for which we have a high number of releases to maintain. The XaaS solution is clearly beneficial overall to maximize margins.

AKF Partners helps companies transition on-premises, licensed software products to SaaS and XaaS solutions. Let us help you on your journey.