As with the word “Cloud”, the word “Platform” is an over-used and far too often underdefined word within our industry (comprised of companies that build technology products delivered online). The lack of a common and unifying definition often leads to conflict in many companies. Often the word “Platform” will mean different things in different contexts. The term almost always means something different from marketing (outside-in) and engineers (inside-out).

As such, companies must define the word for various contexts before attempting to establish a vision or milestones to meet that vision. Failure to define platform end to end will lead to conflict between your most critical teams. In turn, this will destroy company value.

As an example of the strife that may result when “platform” is not defined well within a company, consider the following points and perspectives:

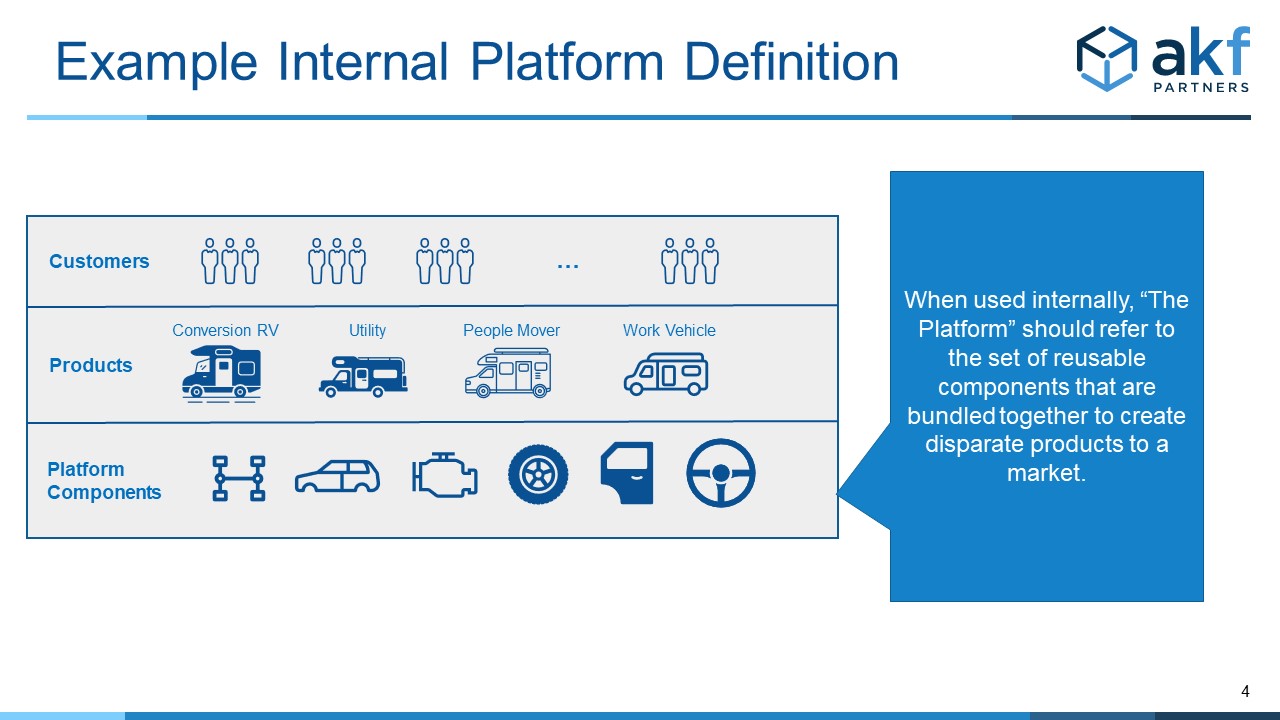

- Architects and engineers may embark on an initiative to develop a platform with an intent to create a set of shared reusable components that can be leveraged across several product offerings within the company.

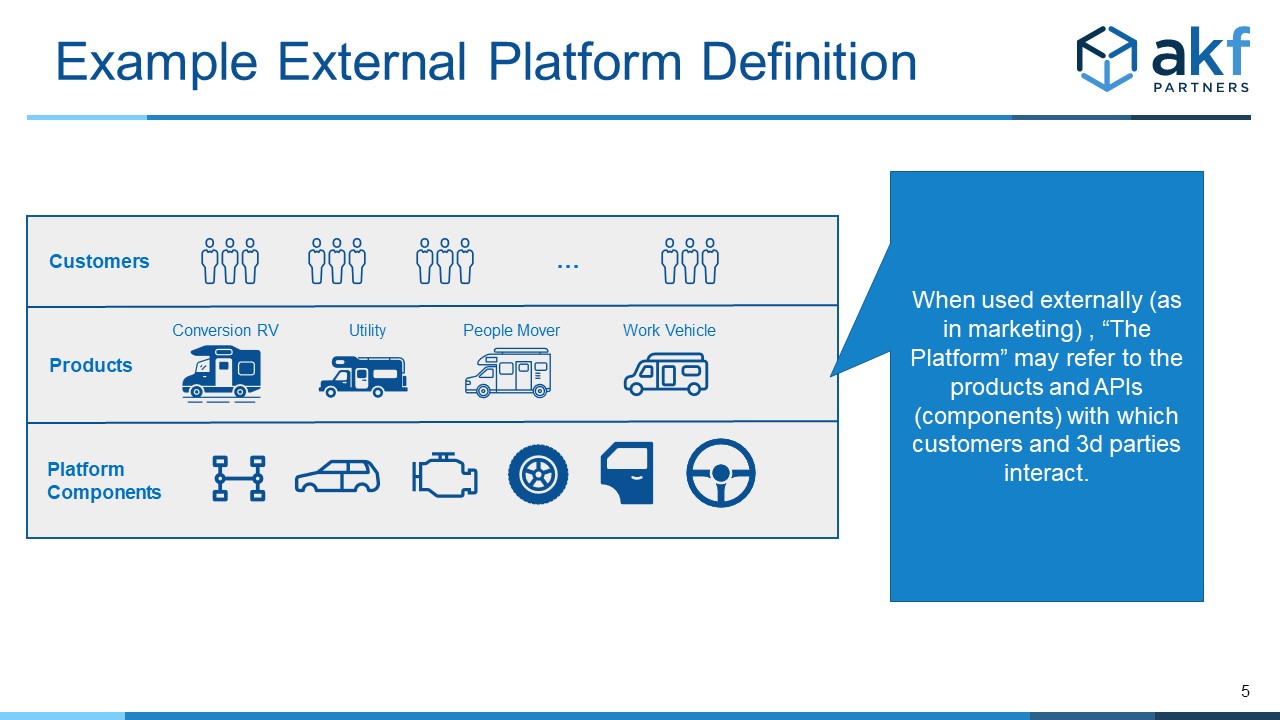

- Product managers may think of a platform as a grouping of componentry that allows core functionality to be easily extended by end customers.

- Marketing teams may consider a platform to be a grouping of customer facing components that can be assembled to create unique products specific to individual industries.

None of these definitions are incorrect, but they are all incomplete. Further note that the definitions don’t agree, which will engender internal conflict that either destroys value or slows delivery.

Different Contexts, Different Meanings

Platform can, and often should, have different meanings dependent upon both audience and context. Below is our (incomplete) list of different definitions for each audience.

Engineering

Engineering teams value platforms because they enable:

- Decreased time to market

- Increased reuse (which aids time to market and quality)

- Decreased cost

- Increased quality.

As such, the engineering definition allows the company to build less overall componentry, thereby decreasing R&D costs and speeding time to market. Very often engineers will see platforms as components that enable products, rather than components that are presented directly to customers.

Product Management and Marketing

Product managers and marketing professionals likely think of Platforms as a:

- collections of assets that can bundled together to create unique products

- system that allows for easy extensibility - either for integrations and/or to create a value multiplying ecosystem (e.g. Salesforce's AppExchange)

- collection of fungible assets (each being easily replaced) that allow for tiered offerings when mixing components

- collection of highly configurable assets, each allowing modification outside of software or infrastructure

Extensibility can be in the form of APIs, SDKs, and/or apps in other Platforms. This extensibility is often done by third parties, partners, professional services teams or by the end customer. Taken to the extreme, the company may create an entire ecosystem and community.

Finance and Capital Markets

CFOs likely see platform as a valuation multiplier. Investors, buy-side and sell-side analysts evaluate the efficacy of of a platform to differentiate a firm within multiple industries and to do so with fast time to market and comparatively low cost.

These personas are trying to determine:

- Does the Platform allow for lower overall cost of operations?

- Does it allow for easy integration and usage by new customers?

- How easily is it integrated with other solutions?

- How easily can 3rd parties extend the platform with capabilities tailored to an end user or business buying/renting the platform?

- Does the ease of integration and need for additional capabilities enable an ecosystem (as in the platform is at the hub) or allow the firm to more effectively play within an existing ecosystem?

The Right Definition of Platform

Because each of the definitions above are both correct and incomplete, the right definition of platform is a union of the above attributes.

Therefore, a software as a service platform consists of discrete components (services and libraries) that enable:

- Reuse of shared components (services or libraries) to reduce cost to develop, time to market, cost of maintenance and quality of service.

- Aggregation of components to present distinct and unique products to end users, either to serve specific industry verticals or to address the needs of various companies as they grow and mature.

- Extensibility of functionality, whether to enable rapid third party bespoke extensions of a product, or to allow for companies to personalize and extend a solution to meet their business processes, wants and needs. Note that this requires well defined, consistent interface points to enable extensions.

- Higher multiples for investors/shareholders and stakeholders through comparatively lower costs to develop, faster time to market, faster market penetration through extensibility and higher levels of quality.

A Useful Platform Analogy

To help prime our platform pump, consider a platform example from an industry that has for a long time capitalized on the “platform” approach.

Remember Lee Iacocca? Lee took over an ailing Chrysler in 1978. Nothing was going well at the company, and it was clearly heading for bankruptcy. In addition to cutting costs and convincing the federal government to underwrite the company, Iacocca turned to a platform strategy to help with cost, time to market, and breadth of product offerings – the Chrysler K platform. The K platform was successful in allowing multiple products (types of cars) to be produced while limiting engineering time and costs. By 1980, the K platform was responsible for Chrysler’s first profit in two years, and by 82 it represented 50% of the company’s operating profits. The K platform met all the following:

- Vehicles comprised of shared components to reduce cost to develop.

- Components intermixed with brands to create at least 10 unique vehicles to end customers.

- Swappable components that allowed for customization and extension of each of the unique vehicles into something somewhat distinct to the end user.

- Allowed Chrysler to secure funding, become profitable and continue operations.

The K platform meets all our platform attributes.

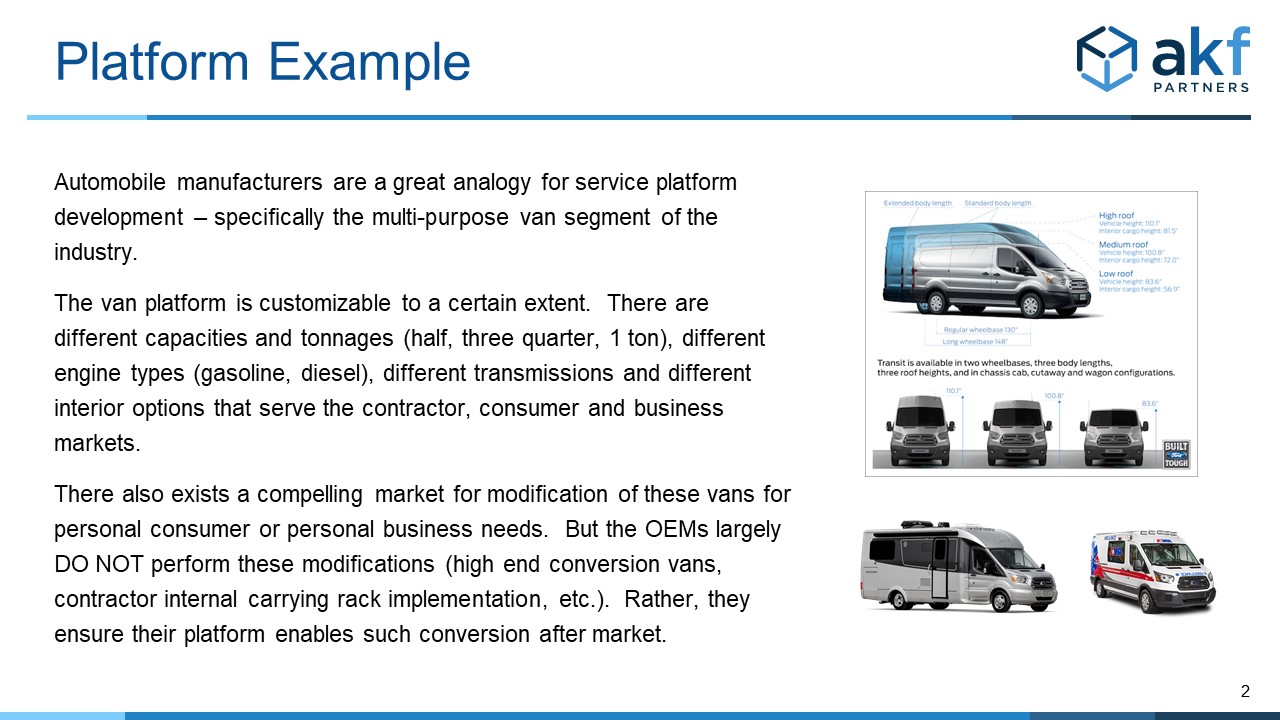

Another platform example we can see today is the van segment as offered by multiple automobile firms including Mercedes and Ford.

This segment also meets our four attributes:

- Wheels, engines, chassis, tops, transmissions, etc.. are all shared components across several different products presented to end customers.

- Components are assembled to create potentially hundreds of configurations of work, pleasure and utility vehicles in various tonnages (e.g. half, ¾ and one ton vehicles).

- Components are extensible and swappable and there exists a thriving aftermarket conversion business for both the RV and utility sectors of the market.

- The segment is so compelling in multiples and profitability that Mercedes, typically a luxury brand, sells near empty shell vans (some may consider this a blemish on the luxurious brand name) alongside fully tricked out passenger vans.

Hopefully the attributes of platform above make it clear that to be successful in a platform endeavor, nearly every organization in the company must change both their mindset and their behaviors.

Our next post will focus on the mindset, behavior, organization and process changes necessary within a company to be successful in a platform transformation or to implement your first platform.

Embarking on a platform initiative – or a transformation of your existing product to a platform? Give us a call – we can help!