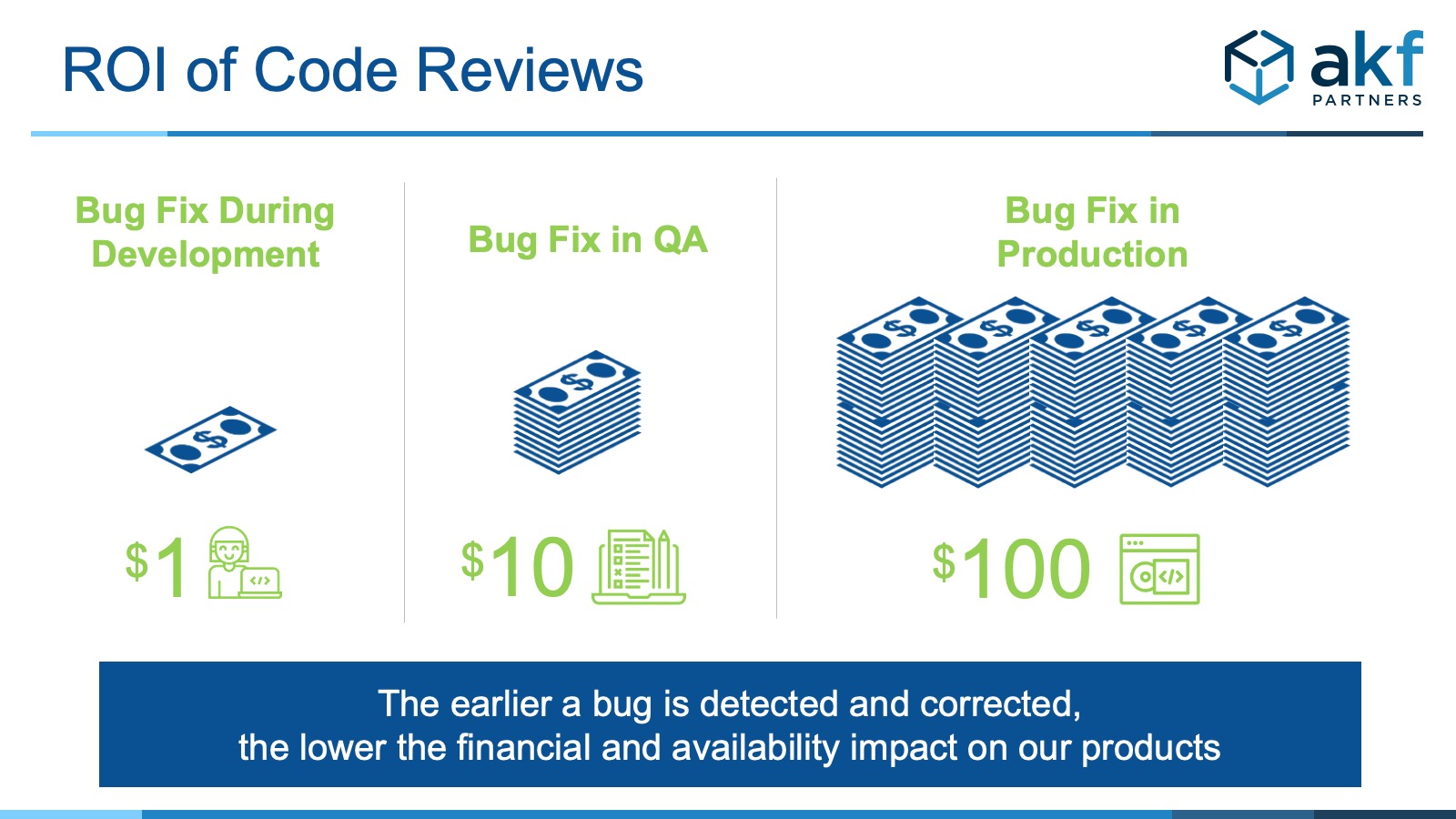

Software engineers have likely heard of the studies that show how the cost of a defect increases by an order of magnitude for each successive phase. If you haven’t heard of these – especially in Waterfall release cycles – if it cost $1 to fix a bug found in development it cost $10 to fix if found in QA and $100 to fix once it is in production.

While Agile development, A/B test releasing, and sharding by customers (and therefore not releasing new code to all customers at once) can reduce the blast radius and cost of fixing bugs, we have seen many shops claiming to be Agile still working in a very "waterfall-ish" way but changing titles to match Agile.

Regardless of the exact costs - this is one reason we consider processes such as unit tests and code reviews as critical to technology organizations. Finding bugs earlier saves money in terms of the effort of the tech teams and no matter how large or small the business, getting the most out of the tech team is vital.

The process that we’re focusing on in this post is code review. The engineers reading this are probably groaning out loud and about to stop reading, but we implore you to read on. Implementing a code review process in the correct manner can not only save the business money but also be a valuable tool for engineering cross training, mentoring, and professional development.

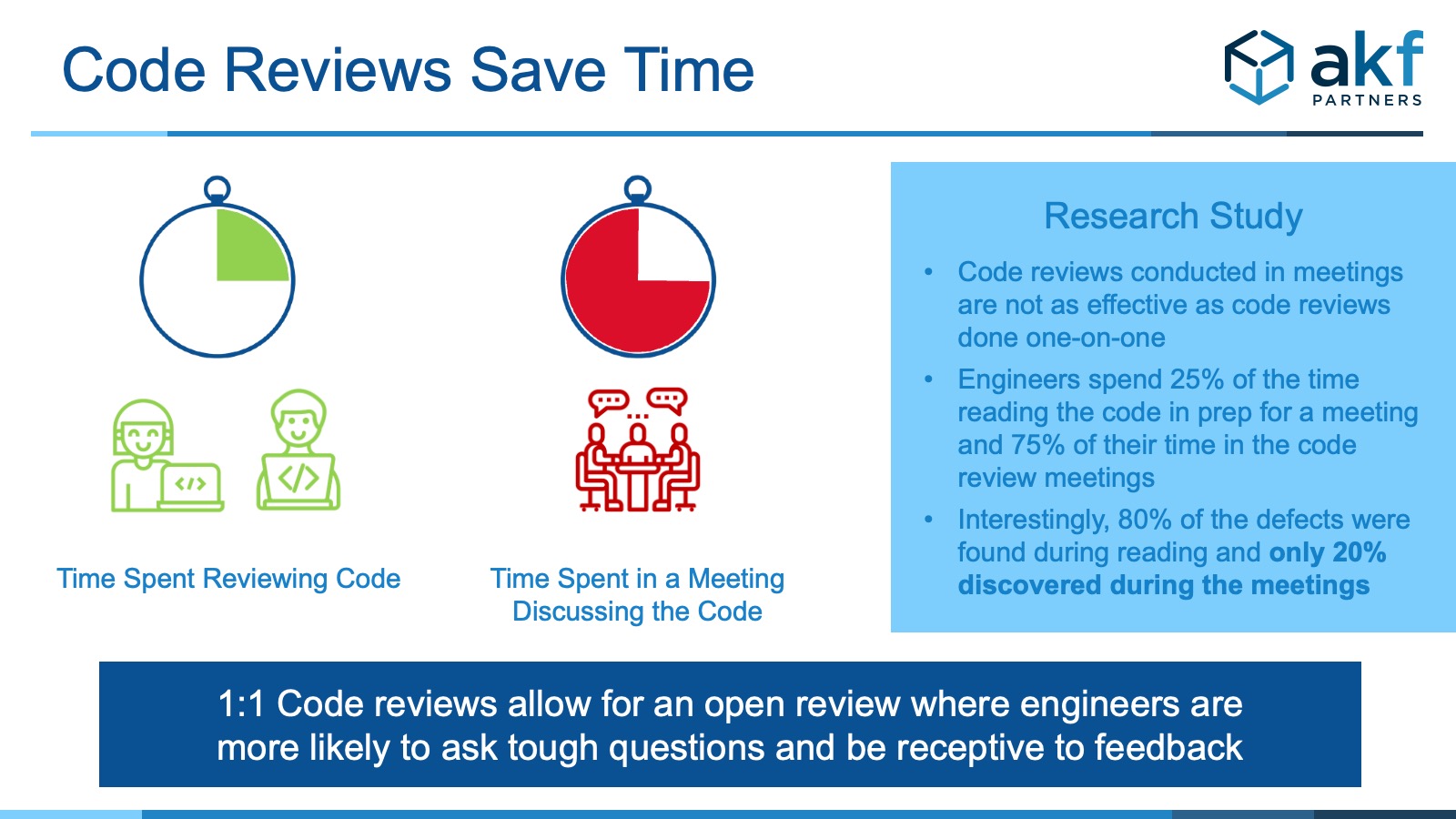

There are many different methods of implementing code reviews from group meetings to paired programming. We have seen many various methods and while any method is better than no code review, the one that we’ve seen the most success as measured by engineering contentment, long term continuation, and defect identification, is the one-on-one peer review.

The engineers reading this are probably groaning out loud and about to stop reading ...

One-on-one peer code review is conducted between two engineers who can interact in person, on the phone or via email. The reviewer typically gets assigned a feature to review prior to the code being promoted to the testing branch. This serves as one of the final steps in development prior to formal testing beginning.

The reason that this individual review is more effective in many ways can be attributed to the general nature of coding which typically involves periods of quiet concentration alone. There is no reason to expect that reviewing code is any different than writing it in the first place.

Secondly, engineers are much more receptive to feedback in private and reviewers are much more likely to ask tough questions via email with the developer as opposed to in a group setting with management present.

A good resource for more details about the benefits of peer reviews is the book “Best kept Secrets of Peer Code Review” by Jason Cohen from Smart Bear, Inc. Admittedly Smart Bear is selling software for peer code reviews but even with this bent the book is a good source of information about studies and the history of code reviews.

In one such study cited in the book that demonstrates why code reviews conducted in meetings are not as effective as code reviews done one-on-one, they determined that engineers spent 25% of the time reading the code in prep for the meeting and 75% of the time in the code review meetings. Interestingly, 80% of the defects were found during reading and only 20% discovered during the meetings.

Whatever code review process you decide to implement, anything is better than not doing it as long as the team has bought into it as a performance and efficiency enhancer.

Consider providing some reading material on code reviews and let one or more of the engineers propose a code review process. Engineers who own the solution are much more likely to be excited about it and follow through on it.

[Much of this post was originally written by Mike Fisher, Founding Partner of AKF]