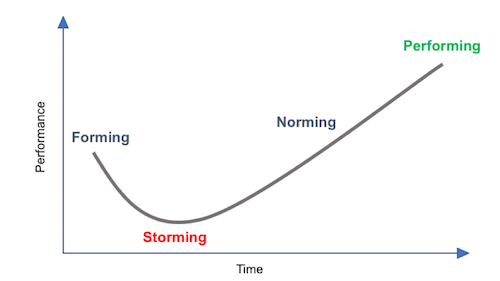

In 1965, psychologist Bruce Tuckman published his theory of group dynamics. This theory describes the stages (or phases) through which a team progresses enroute to optimal productivity. While generally useful for any organization, and prescriptive as to what leaders should do when to boost performance, it has profound impacts to Agile development practices and how we build organizations around these Agile practices.

Forming

The first stage is forming. This is where the team first comes together. Here, the individuals are trying to get to know each other. They tend to be polite and cordial, but they do not fully trust each other.

In this stage, the team productivity and team conflict are low. The team spends time agreeing to what the team is supposed to do. This lack of agreement of the team’s purpose can cause members to miss goals because they are individually targeting different things. Team members rely on patterned behavior and look to the team leader for guidance and direction. The team members want to be accepted by the group. Cautious behavior on the part of the team starts to depress overall team outcomes. Good leadership, emphasizing goals and outcomes is important to set the stage for future team behaviors and outcomes.

Storming

Once the team’s goals are clear, they move into the next stage, storming. Here, the team starts to develop a plan to achieve the goal and defines what to do and who does it. Friction starts to occur as members propose different ideas. Trust within the team remains low and affective conflict rises as people vie for control. Cliques can form. Productivity drops even lower than in the first stage.

Once the team agrees on the plan and the roles and responsibilities, it can move to the next stage. Without agreement, the team can get stuck. Symptoms include poor coordination, people doing the wrong things and missing deadlines, to name a few. Good leadership here focuses on fast affective conflict resolution, and serves to help reinforce team goals and outcomes in order to quickly move to more productive phases.

Norming

Once team members agree to the plan and understand their roles, they enter the norming phase. Affective conflict goes down, cognitive (beneficial) conflict and trust increase. The team focuses on how to get things done and productivity begins to increase. The team develops “norms” about how to work together and collaborate. A lack of these norms can cause issues such as low quality and missed deadlines.

Leadership within the team becomes clear and cliques dissolve. Members begin to identify with one another and the level of trust in their personal relationships contributes to the development of group cohesion. The team begins to experience a sense of group belonging and a feeling of relief from resolving interpersonal conflicts. Team identity starts to take hold and innovation and creativity within the team increases. The members feel an openness and cohesion on both a personal and task level. They feel good about being part of the team.

Performing

The final stage, preforming, is not achieved by all teams. This stage is marked by an interdependence in personal relations and problem solving within the realm of the team’s tasks. Team members share a common goal, understand the plan to achieve it, know their roles and how to work together. The team is firing on all cylinders. At this point, the team is highly productive and collaborates well. They are trusting of each other and “have each other’s back.” Healthy conflict is encouraged. There is unity: group identity is complete, group morale is high, and group loyalty is intense.

Not all teams get to this phase. They can get stuck in a previous phase or slide back into them from a higher phase. Leadership that focuses on affective conflict resolution, team identity creation, a compelling vision and goals to achieve that vision is critical to reaching the Performing phase. It is usually not easy for teams to quickly progress through these stages, and it often takes 6 months or more for a team to reach the Performing phase.

Impact to Agile Development

We often see companies make the mistake of coalescing teams around initiatives. Sometimes called “virtual teams” or “matrixed teams”, these teams suffer the underperforming phases of Tuckman’s curve repeatedly, especially when these initiatives are of durations shorter than 6 months. But even with durations of a year, six months of that time is spent getting the team to an optimum level of performance.

Tuckman’s analysis indicates that teams should be together for no less than a year (giving a 6 month return on a 6-month investment) and ideally for about 3 years. The upper limit being informed by the research on group think and its implications to creativity, performance and innovation within teams. Teams then should become semi-permanent and we should seek to move work to teams rather than form teams around work. To be successful here, we need multi-disciplinary teams capable of handling all the work they may get assigned. Further, the team needs to be familiar and “own” the outcomes associated with the solution (or architectural components) with which they work. More on that in future articles discussing Conway’s Law and Empathy Groups.

AKF Partners helps companies understand and apply the extant theory around organizational development in order to turbo-charge engineering performance. Wondering if your engineering productivity decreases as you grow your engineering and product teams? We can help you fix that and get your productivity back to the level it was as a startup!